A bajada is the mound of run-off sediment skirting the edge of the mountain. It is not quite Spanish for “Alluvial Fan”, but they are functionally the same thing.

The Bajada Trail winds up and across its namesake across the San Juan Valley in the Phoenix South Mountain preserve. Or, rather, the main western portion des this. The eastern third of the trail is basically a connector trail we have written about elsewhere.

The portion we write about here connects the San Juan Bicycle Center with the San Juan Lookout, running from its junction with the Max Delta Trail (at the lot) to its’ junction with the National Trail on the west end of the park. You then follow the National Trail northwest to the lookout.

This is often done as a loop hike with the Alta Trail. If so, regardless of direction, do Alta is the harder of the two, and I always recommend doing the hard part first. If you do it as a loop, take a lunch.

I did this as a car shuttle. My plan was to park at the bike lot, and then have a friend drive me to the Curtis Saddle Trailhead. However, we lucked into one of those Brigadoon-like morning when the vehicle road to San Juan Lookout was actually open to actual vehicles. So, he dropped me off there instead.

The route is National Trail of Bajada Trail to the bike center – a route that is about 4.3 miles one way. Most people can do it in a couple of hours.

National Trail heading out from the lookout is what you picture single-track trail through the low desert to look like: Packed dirt wide enough for one pedestrian, winding through the cactus. There are not a lot of landmarks. Sure, to the west, AZ 202 crosses in front of the casino, but the trail itself has few features. The junction with the Maw Ha Tuak Perimeter Trail. A stand of teddy-bear cholla. A stand of chain fruit cholla. A stand with both of them together. A geologic marker. You cross three small washes, then a big one, and then East San Juan Road. On the far (south) side of that you come to the junction with the western terminus of the Bajada Trail.

The National Trail, also called the Maricopa Trail heads off further southwest until it turns east and charges up the main Gila Range to the top ridge. It will continue east across that ridge to the other end of the park.

I took the Bajada Trail, of course. It promptly crossed the grey-gravel expanse of the main San Juan wash, and then began a lesser climb up the mountain, turning east kinda-sorta along the top of the bajada.

When the road is closed, and you get some distance from the freeway, this is one of the quietest sections in the park.

The trail will go up the berm and down the wash and up the berm for most of its remaining length (either direction). It is in excellent shape, a little rocky in places, blue and black basalt with a little gypsum for color, but you can do this in tennis shoes. The entire length is a shadeless march through stunted palo-verde trees, bone dry creosote and a scattering of cacti.

The terrain is not your problem. Like all hikes in this park, or this area, do not attempt this in summer unless you start marching in the predawn gloom. The entire hike I noted two places (both washes) with enough shade that a grown human could sit down within.

Below you (north) East San Juan Road follows the wash through the relatively quiet canyon. Towards the end, after one of the few sustained climbs, the trail with turn north and descend towards the road. Before you get there, as you start to enter the main wash, you will reach the junction with Alta Trail.

You are a half-mile from the trailhead. You can guzzle some water now.

Don’t cross the wash. Stay on Bajada as it turns east again, though and then out of the wash. Then across the desert floor a little farther to pavement.

If you look up the hill during this passage you will see mine trailings, and perhaps some social trails going up towards same. There is at least one open mine shaft still existing on those slopes, but you are on your own with that. When crawling about in mine-shafts, you are betting your life on the engineering acumen and diligence of whatever miner dug this 100+ years ago, and I cannot recommend that.

The bike lot has trashcans, but no other services. The San Juan Lookout has nothing but an old ramada and signage.

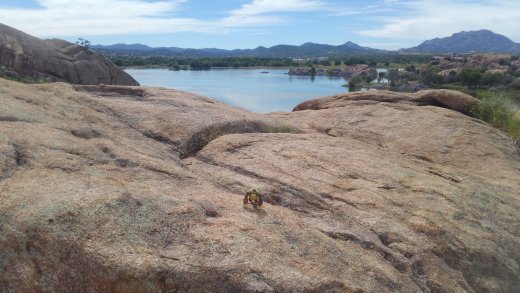

It will dip in and around some wooded washes before reaching McCasland Park, where I found the water and restrooms nearly life-saving. Past there the trail wanders through scrub along the shore, passing Embry-Riddle University on the far side of the road, and finally back to the city park sprawling along the north shoreline.

It will dip in and around some wooded washes before reaching McCasland Park, where I found the water and restrooms nearly life-saving. Past there the trail wanders through scrub along the shore, passing Embry-Riddle University on the far side of the road, and finally back to the city park sprawling along the north shoreline.